Other Digital Projects

As we began working on our project, we explored and drew ideas from a number of other digital projects. We’ve highlighted a sampling of these below.

Mapping Cville

This ongoing project for the Jefferson School African-American Heritage Center (JSAAHC) “maps inequities in Charlottesville from past to present.” Led by Jordy Yager and funded by a grant from the Charlottesville Area Community Foundation, Mapping Cville “will live online, as an exhibition at the JSAAHC, and as part of a broader curriculum unit in area schools. It will have many different maps and layers for people to interact with, so that we can see how the patterns and decisions of the past impact our realities and outcomes today. Through maps... we can begin to see the bigger, more complicated, structures and decisions that have gotten us to where we are today — so that we may better think about where we want to go tomorrow.”

Housing the University: Student Housing and Displacement in Charlottesville, Virginia

This is a student project that “examines the changing relationship between UVA and the City of Charlottesville through the lens of housing.” It was produced by Brian Cameron, Morgan Felenkris, and Allie Arnold as part of “All Politics is Local,” a year-long seminar at UVA that was co-taught by Sarah Milov and Andrew W. Kahrl in 2017-18.

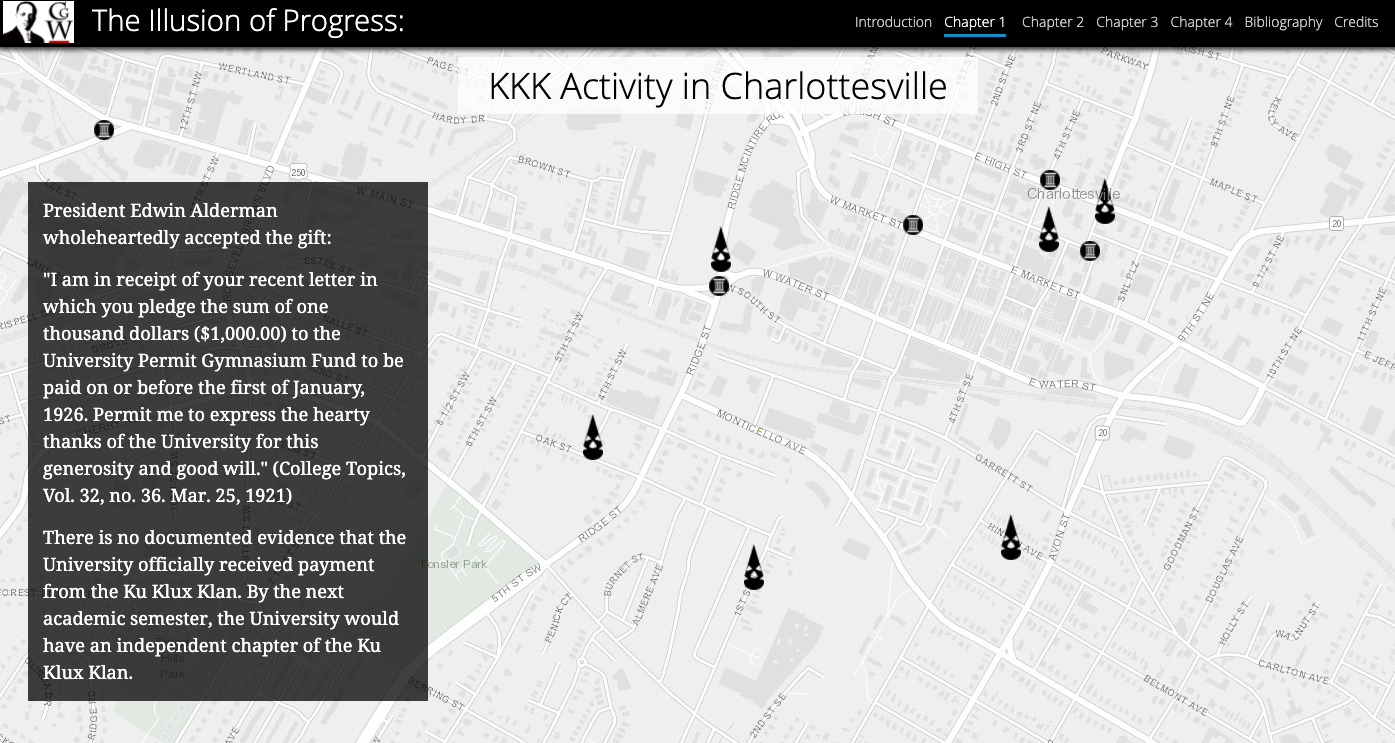

The Illusion of Progress: Charlottesville’s Roots in White Supremacy

“Throughout the summer of 2017, the Citizen Justice Initiative team researched the history surrounding Charlottesville’s Confederate statues to create a StoryMap entitled ‘The Illusion of Progress: Charlottesville’s Roots in White Supremacy.’ The resource builds on extensive work by members of the Charlottesville and University community, who collected sources, made presentations, wrote think pieces, and created syllabi to educate onlookers, activists, and curious citizens about the roots of white supremacy locally and beyond. It also sources past projects on local history to make previous research on Charlottesville, the University, and Virginia relevant to the resurgence white supremacist activity today.”

The Cultural Landscape of Birdwood

“The Cultural Landscape of Birdwood” is a project by UVA School of Architecture students, run from 2016-18, which tells the story of the Birdwood plantation and manor to the west of Charlottesville (the manor is now owned by the UVA Foundation, which approached the project early on for information about parcels of land on which it intended to create a golf course). The project uses laser scanning, 3D modeling, and ground-penetrating radar, among other technologies, to create an interactive history of the site.

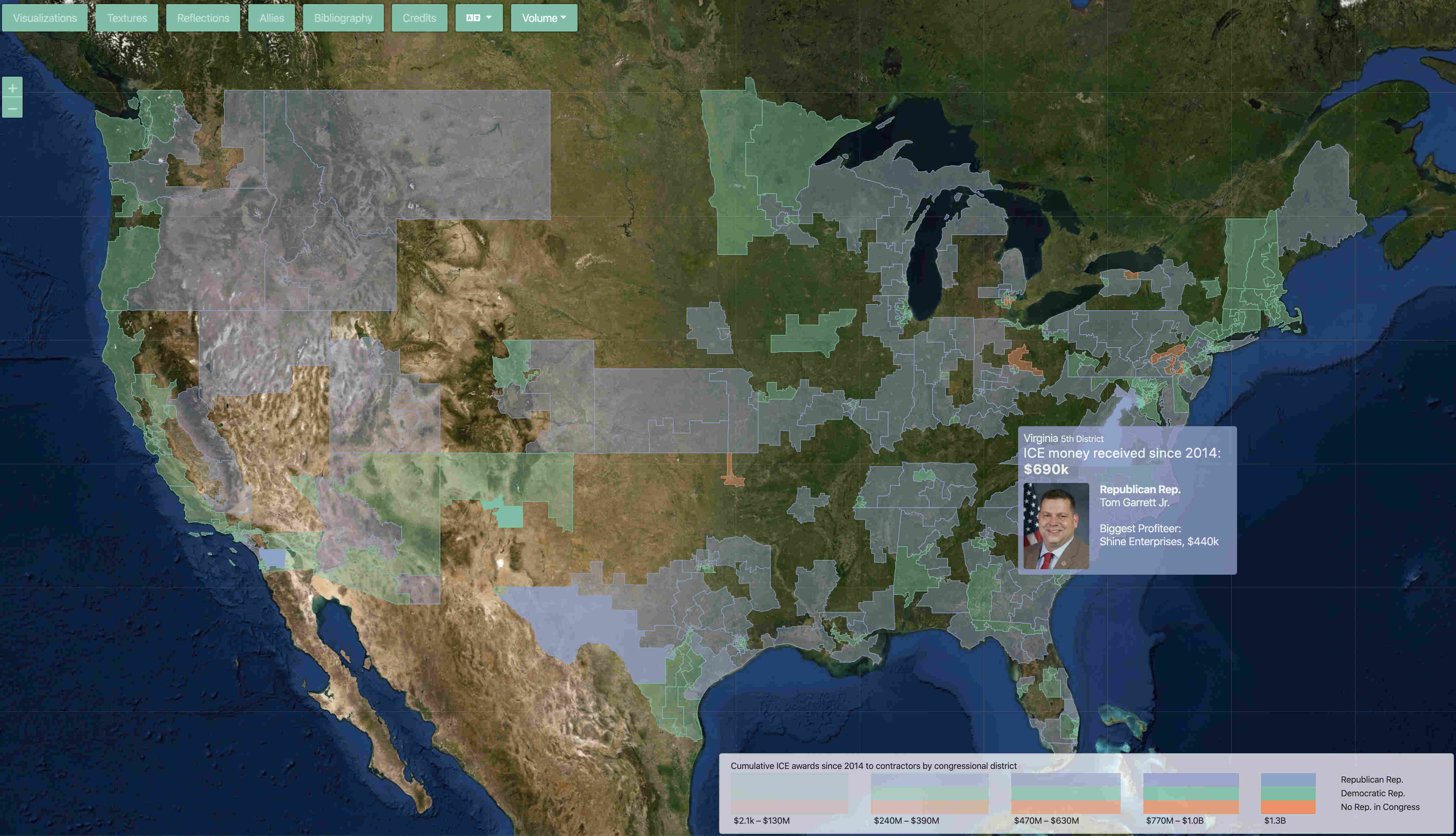

Torn Apart / Separados

Torn Apart / Separados Volume 1 is a “rapidly deployed critical data & visualization intervention in the USA’s 2018 ‘Zero Tolerance Policy’ for asylum seekers at the US Ports of Entry and the humanitarian crisis that has followed.” Torn Apart / Separados Volume 2 “is a deep and radically new look at the territory and infrastructure of ICE’s financial regime in the USA. This data & visualization intervention peels back layers of culpability behind the humanitarian crisis of 2018.”

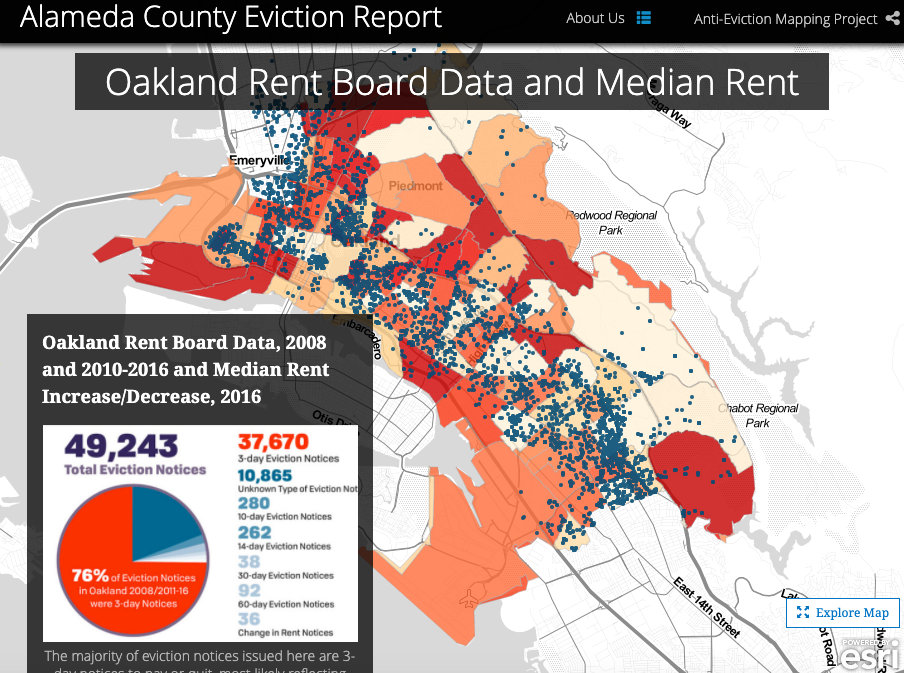

Anti-Eviction Mapping Project

“The Anti-Eviction Mapping Project is a data-visualization, data analysis, and storytelling collective documenting the dispossession and resistance upon gentrifying landscapes. Primarily working in the San Francisco Bay Area, Los Angeles, and New York City, we are all volunteers producing digital maps, oral history work, film, murals, and community events. Working with a number of community partners and in solidarity with numerous housing movements, we study and visualize new entanglements of global capital, real estate, technocapitalism, and political economy. Our narrative oral history and video work centers the displacement of people and complex social worlds, but also modes of resistance. Maintaining antiracist and feminist analyses as well as decolonial methodology, the project creates tools and disseminates data contributing to collective resistance and movement building.”

Land Grab Universities

“Nearly 11 million acres of Indigenous land. Approximately 250 tribes, bands and communities. Over 160 violence-backed treaties and land seizures. Fifty-two universities. With [this project], you can untangle the powerful and painful strains of myth and money behind the land-grant university system, which broadened access to higher education in the United States.”

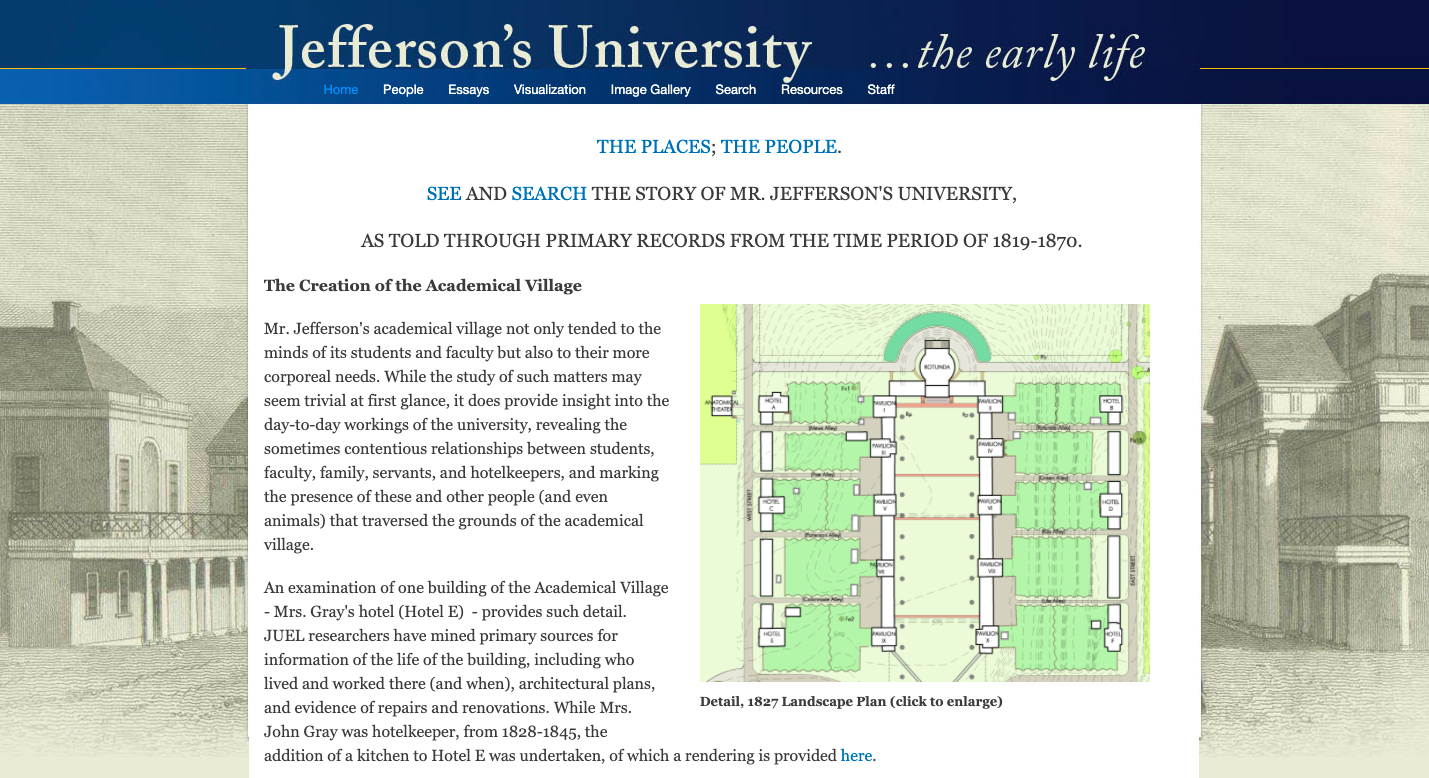

Jefferson’s University—Early Life Project, 1819-1870 (JUEL)

The Jefferson’s University—Early Life Project, 1819-1870 (JUEL) website is “a place to encounter what life was like in the first years of the University of Virginia. Jefferson’s vision of a secular university, dedicated to enriching public life and sustaining the new republic, was both embodied in and transformed by the people who lived, worked, and studied at the University. Bringing together a trove of personal and administrative documents, as well as archival images of the university and three-dimensional digital renderings, JUEL invites users to discover the people and places of the University’s early years, stretching from its founding in 1819 through the end of the Civil War.”

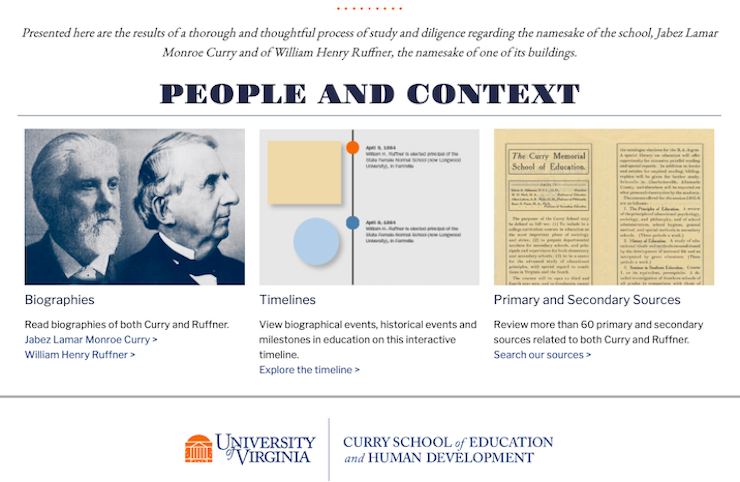

Who and How We Memorialize

“More than two years ago, the faculty and leadership of the Curry School of Education and Human Development began a process of diligence inquiry into the namesake of the school, Jabez Lamar Monroe Curry and of William Henry Ruffner, the namesake of one of its buildings. As part of that process, this website presents information gathered during a thorough process of study regarding both J.L.M. Curry and W.H. Ruffner conducted by the Curry School of Education and Human Development Ad Hoc Committee on Naming, an informational and temporary committee formed by Bob Pianta, Dean of the Curry School.”

Finding the Enslaved Laborers at UVA

“This page is for Finding the Enslaved laborers who built the University of Virginia. If you have or believed to have enslaved ancestors that lived near and around the University of Virginia please contact us. The area is the city of Charlottesville and the surrounding counties of Albemarle, Louisa, Nelson, Fluvanna, Greene, Buckingham, Orange, and throughout Virginia.”

Black Fire at UVA

Black Fire is “a multimedia initiative documenting the struggle for social justice and racial equality at the University of Virginia... This multimedia initiative is sponsored by UVA’s Office of the Vice Provost of the Arts and organized by Professors Kevin Jerome Everson of the Department of Art and Claudrena N. Harold of the Carter G. Woodson Institute for African-American and African Studies and the Corcoran Department of History.”

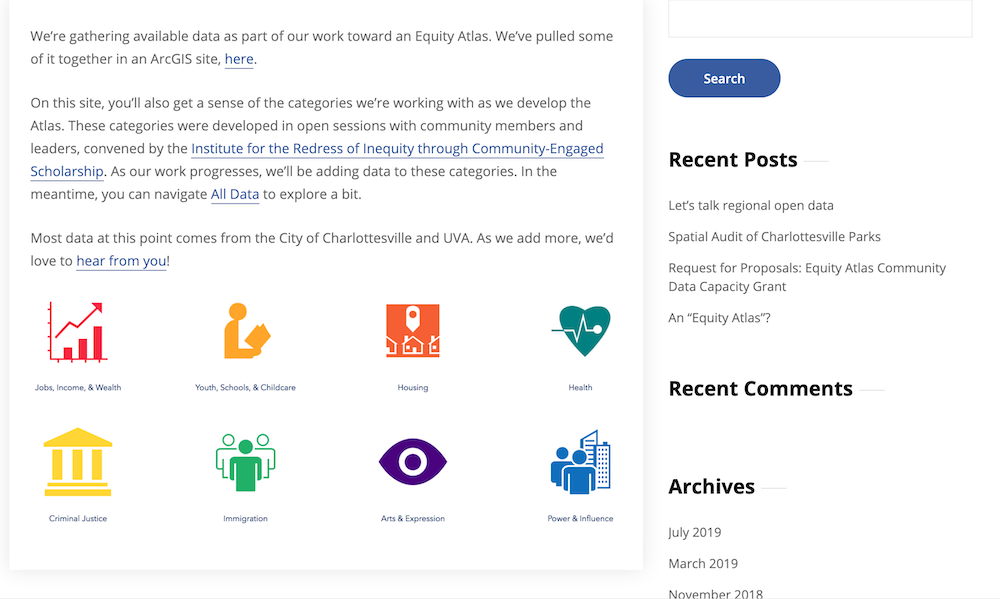

Charlottesville Equity Atlas

The Charlottesville Equity Atlas uses mapping data and information “to build the foundation for a collaborative tool that is inclusive of the voices, work, and expertise of our regional community.” The project aims to provide data on housing, health, schools, jobs, health, criminal justice, immigration, and more.

Race and Place: African American Community Histories

The Race and Place project gathers various digital archives relating to African-American history in the United States, covering the age of slavery (including materials from the American Civil War), Reconstruction, and the Jim Crow South.

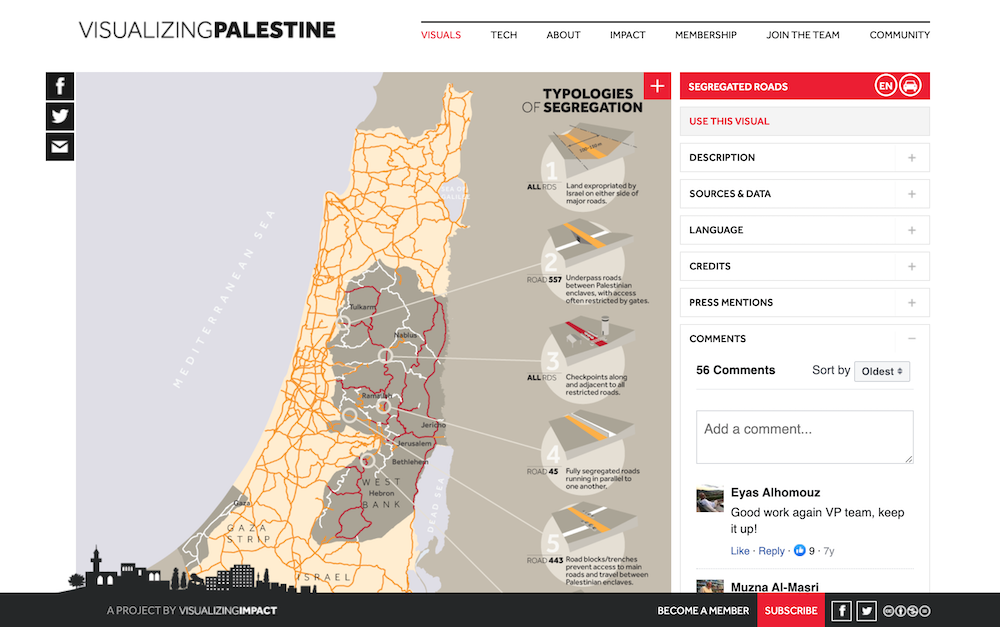

Visualizing Palestine

“Visualizing Palestine creates data-driven tools to advance a factual, rights-based narrative of the Palestinian-Israeli issue. Our researchers, designers, technologists, and communications specialists work in partnership with civil society actors to amplify their impact and promote justice and equality.”

Race and Repair at the University of Virginia

“The project aims to deepen the knowledge of the University of Virginia community of its own racially charged history. It maps the places on and surrounding the University’s Grounds that are physical manifestations of this history and in many cases are vestiges that remain from more troubled times.” Though the website’s “Explore” link no longer functions, you can now access the digital map in ArcGIS.

Monument Lab

“Monument Lab is an independent public art and history studio based in Philadelphia. Founded by Paul Farber and Ken Lum, Monument Lab works with artists, students, activists, municipal agencies, and cultural institutions on exploratory approaches to public engagement and collective memory. Monument Lab cultivates and facilitates critical conversations around the past, present, and future of monuments.”

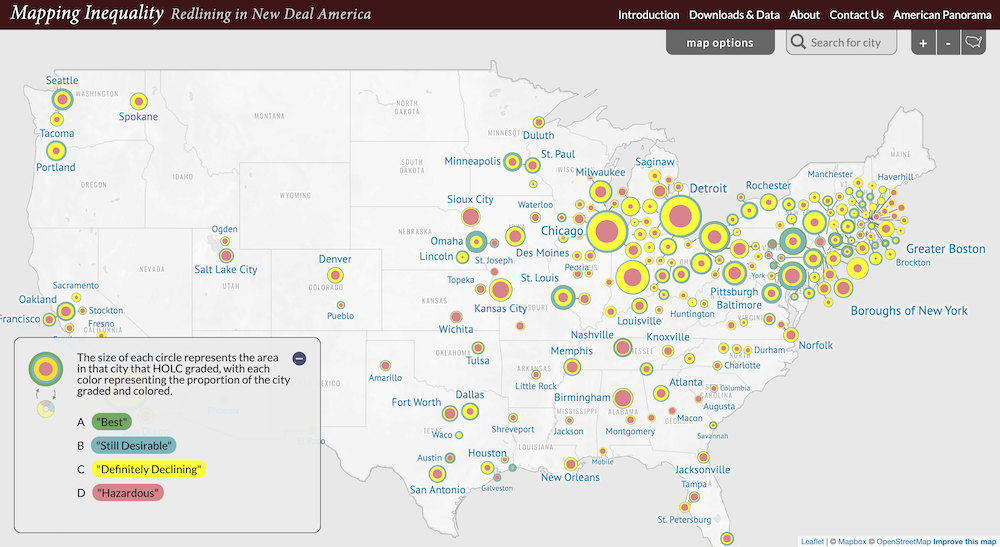

Mapping Inequality

A collaborative project across four universities, Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America uses “security maps” produced by the Home Owners Loan Corporation to allow users to visualize how governmental housing policies contributed to residential segregation and wealth inequality. It shows how “real estate appraisers used the apparent racial and cultural value of a community to determine its economic value” and “provides visitors with a new view, and perhaps even a new language, for describing the relationship between wealth and poverty in America.”